Computers and Automation Vol 18 No 9 August 1969 Computer Art

First-Hand:Early Digital Fine art At Bell Phone Laboratories, Inc

From ETHW

Spring to:navigation, search

Copyright [edit | edit source]

Written by A. Michael Noll, February 2d, 2014

Copyright © 2014 A. Michael Noll

This history by A. Michael Noll was published in LEONARDO, the official periodical of the International Society for the Arts, Gild and Applied science: "Early Digital Calculator Art at Bong Telephone Laboratories, Incorporated," LEONARDO, Vol. 49, No. 1 (2016), pp. 55-65.

Abstract [edit | edit source]

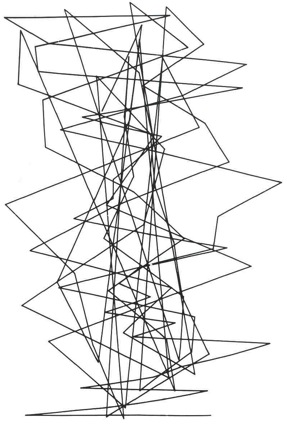

Fig. 1. Gaussian-Quadratic. Copyright © 1965 A. Michael Noll. "Gaussian-Quadratic" is an case of algorithmic art. Coordinates along the horizontal axis are chosen by a pseudo-random Gaussian subroutine, while coordinates forth the vertical axis are chosen by a quadratic equation. When a coordinate reaches the acme, information technology is reduced modulo 1024 to begin to climb vertically again. This paradigm reminded Noll of Picasso's "Ma Jolie" which he liked at the Museum of Modern Art. "Gaussian-Quadratic" was created in 1962-63 every bit the culmination of a serial of such images in which the parameters of the algorithms were varied. It was exhibited at the Howard Wise Gallery in 1965 – which determined the copyright date. The slice was registered at the U. South. Copyright Function.

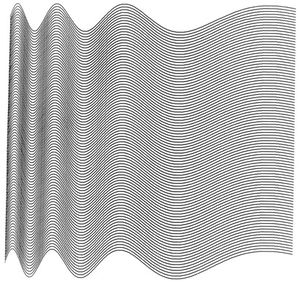

Fig. ii. "Xc Parallel Sinusoids" past A. Michael Noll is based on Bridget Riley'southward op-art "Currents." It is algorithmic art and showed how easily a digital computer could be programmed to create such fine art.

Fig. 3. Leon Harmon and Kenneth Knowlton created "Gargoyle" in 1967 by digitizing a photo of a gargoyle at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris into diverse grey levels then assigning different 15-past-15 little micro-images of a wide variety of objects to each gray level. In effect, this was a reckoner-generated mosaic, using small images rather than tiles to represent gray scale values. This photo shows Knowlton looking at the big computer-generated mosaic.

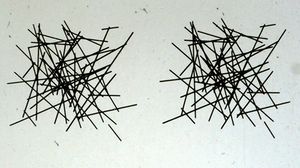

Fig. four. A stereographic pair (programmed by A. Michael Noll) of lines placed at random in a 3D space. The 3D outcome can be accomplished if the left prototype is viewed by the left eye and the right prototype by the right centre. Since in that location are no monocular depth clues, stereoscopic viewing is the just way to obtain whatever 3D data.

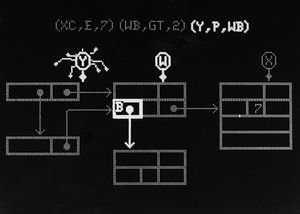

Fig. 5. Single frame from the reckoner-animated pic "Simulation of a Ii-Gyro Gravity-Gradient Mental attitude Control System" by Edward E. Zajac. The pic was created past Zajac in 1963 using the FORTRAN programing language and drawn on the Stromberg-Carlson SC-4020 microfilm plotter. The small clock in the upper right counts the number of orbits. This film was one of beginning computer-animated movies made at Bell Telephone Laboratories, Inc., although others then made many more at Bell Labs.

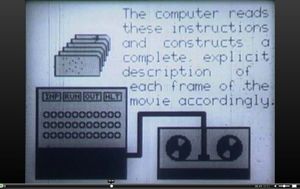

Fig. half dozen. Still frame from the computer-animated moving picture "A Computer Technique for the Production of Animated Movies" by Kenneth C. Knowlton, begun in 1963 and finished in 1964, using Knowlton'south BEFLIX programming language and a Stromberg-Carlson SC-4020 microfilm plotter. This was Knowlton's earliest computer blithe movie and led into his after collaborations with various artists.

Fig. 7. Still frame from the reckoner-animated film "PoemField No. 2" mde past Stan VanDerBeek and Kenneth C. Knowlton in 1966 using Knowlton's BEFLIX programming language. The film was created in a collaborative manner, with Knowlton responsible for the figurer programming, including the writing of macros that VanDerBeek used for some of the animations. VanDerBeek edited the sequences together and had them colorized. VanDerBeek had an interest in words, and thus at the very starting time he started with the idea of poems. An IBM 7094 chief-frame digital computer was used and the images were plotted on the Stromberg-Carlson SC-4020 microfilm plotter. The film can be seen at the AT&T Tech Channel at: http://techchannel.att.com/play-video.cfm/2012/8/13/AT&T-Archives-Poem-Field-two

Fig. viii. Stereoscopic pair from A. Michael Noll'due south reckoner-animated motion-picture show of the three-dimensional projection of a rotating iv-dimensional hypercube. Noll subsequently placed words in four-dimensional space and created computer-blithe films of their rotation projected ultimately to two dimensions. The complete motion-picture show is at YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iXYXuHVTS_k

Fig. 9. A frame from Kenneth C. Knowlton's computer-animated moving-picture show about how to use his L6 programming language. A piddling beetle-similar shape moves virtually the screen. An arbitrarily complex spider web of pointers and information is congenital and managed by beetle-like pointers that navigate throughout the network.

Fig. x. Computer Composition With Lines. Copyright © 1965 A. Michael Noll. "Computer Composition With Lines" was created algorithmically with pseudo-random processes to mimic Piet Mondrian's "Limerick With Lines." Copies of both works were shown to people, a majority of whom expressed a preference for the reckoner work and idea it was past Mondrian – which became a archetype experiment in aesthetics. The piece of work won showtime prize in August 1965 in the contest held by Computers and Automation mag.

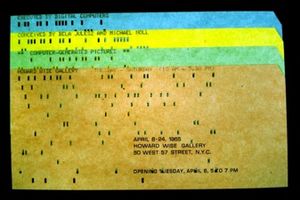

Fig. 11. An early exhibit of Noll's digital art was held at the Howard Wise Gallery in 1965, forth with patterns created by Bela Julesz as stimuli in his investigations of stereoscopy. The announcement for the show was a pocket-size deck of IBM cards, shown here.

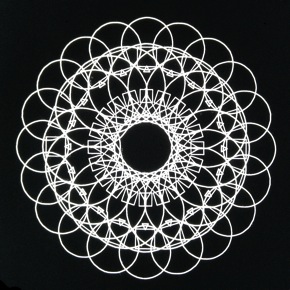

Fig. 12. Computer art created by Aaron Marcus in 1967 using the GE 635 mainframe figurer and Stromberg Carlson SC-4020 microfilm plotter. The program was written in FORTRAN and allowed for easy variation of angles of rotation, sizes of shapes, and choices of combination of shapes. This series of computer-art images explored the visual furnishings of symmetry and the use of repeated uncomplicated shapes to create visual complexity. [Courtesy of Aaron Marcus and A. Michael Noll]

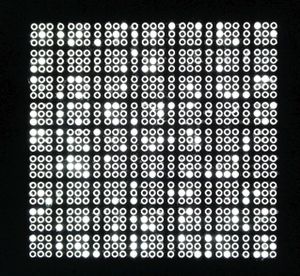

Fig. 13. The lights representing commands and/or data in the computer's key processing unit of measurement, which were actively displayed on the "dashboards" of computers in the 1960s and 70s, inspired this 1967 computer-art paradigm by Aaron Marcus. The program immune for variation of which buttons would be lighted and which would be dark according to random-number generators. [Courtesy of Aaron Marcus and A. Michael Noll]

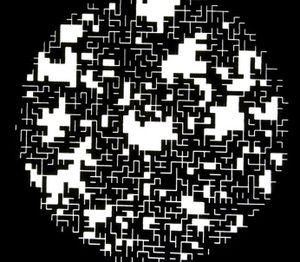

Fig. 14. This computer-art paradigm by Aaron Marcus in 1967 explored the visual furnishings of random filling in of a filigree of lines and solid areas inside that filigree according to the results of a random-number generator. The objective was to create visual complication and images that accept a somewhat handcrafted antiquity quality equally well as a high-tech manner, typical of both mod art and aboriginal artifacts from thousands of years ago. [Courtesy of Aaron Marcus and A. Michael Noll]

This commodity is a history, of the digital calculator art and animation that was adult and created at Bell Telephone Laboratories, Incorporated (or merely, Bong Labs) from 1962 to 1968. Still and blithe images in 2 dimensions and in stereographic pairs were created, along with their use in investigations of aesthetic preferences and their application to film titles and choreography. Interactive digital computer music software was extended to the visual domain, including a real-time interactive system. Some of the art works generated were exhibited publicly in major art venues in 1965, and then many were shown extensively in subsequent years. This pioneering piece of work at Bell Labs was a significant contribution to digital art.

Introduction [edit | edit source]

Early pioneering research into digital computer art and artistic animation was done at Bell Phone Laboratories, Inc. at its Murray Hill, NJ facility during the 1960s. This commodity is a history of that research at Bell Labs, focusing on the formative menses from 1962 to around 1968. The emphasis of this history is on the actual employees of Bell Labs who contributed to both the digital art and the engineering.

By the belatedly 1960s, digital computer art was fairly well established, with artists, animators, and conferences around the planet – although every bit a engineering-based fine art medium, it continued to evolve thereafter both with the applied science it employed and with the aesthetics of the era. Given all of today's extensive use of computer graphics, it is hard to imagine that in the 1960s the utilize of graphics every bit output from computers was novel and innovative.

The history in this article is concerned solely with the early work that was performed at Bell Telephone Laboratories, Inc. related to the visual arts. Nonetheless, others likewise did early piece of work in computer art and animation during the 1960s, such as Frieder Nake and Georg Nees in Federal republic of germany, Leslie Mezei in Toronto[1], John Whitney, Sr., and William Fetter at Boeing. Conferences were being held and books were being written by the second half of the 1960s, such as the one organized in 1966 by Martin Krampen at the University of Waterloo in Canada,[2] the 1968 book and exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity by Jasia Reichardt in London,[three] and Tendencies four: Computers and Visual Research in Zagreb in 1968.The Figurer Arts Society first met in London in 1968. [4]

Bell Phone Laboratories, Incorporated (or simply, "Bell Labs") was the research and evolution entity for AT&T's Bong System. AT&T and the Western Electric Visitor (the manufacturing entity for the Bong System) jointly endemic Bell Labs. The bones research done at Bell Labs was roughly about five percent of its work and was mostly financially supported by AT&T and the local phone companies. Dr. William O. Baker was Vice President, Enquiry and Dr. John R. Pierce was Executive Director of the departments where well-nigh of the research in digital art was performed.[5] [half-dozen] These two individuals are featured in two recent books about Bell Labs, and their back up of digital fine art and animation was crucial.

The piece of work in digital art at Bong Labs was both an application from research in calculator graphics and also a stimulus for that inquiry. As an R&D organisation, Bell Labs was keenly interested in the display of scientific data and besides in computer graphics as a form of homo-machine communication.

The Beginnings of Estimator Art: Withal Images [edit | edit source]

Computer graphics was a powerful means of displaying scientific and technological data calculated past a digital computer at Bong Phone Laboratories in the early 1960s. The data were plotted on 35-mm flick by a Stromberg Carlson SC-4020 microfilm plotter, controlled by an IBM 7090 mainframe digital computer. Early on digital computer fine art at Bell Labs evolved from this scientific and technological foundation.

During the summer of 1962, A. Michael Noll (the author of this paper) had an assignment working in the research division of Bell Phone Laboratories, where he was employed as a Fellow member of Technical Staff. His summer project involved the programming of a new method for the determination of the pitch of human being oral communication – the brusk-term cepstrum. The results of the computer calculations were plotted on the Stromberg Carlson SC-4020 microfilm plotter.

The SC-4020 plotter had a cathode ray tube that was photographed automatically with a 35-mm camera. The SC-4020 was intended as a high-speed printer in which the electron beam was passed through a graphic symbol mask and the shaped beam positioned on the screen while the shutter of the camera remained open. The staff of the figurer center wrote a FORTRAN software package to interface with the SC-4020 in positioning the electron beam to draw images on the screen, mostly plots of scientific information, with a 1024-past-1024 resolution.

A colleague (Elwyn Berlekamp) had a programming error that produced a graphic mess on the plotter, which he comically chosen "estimator art." Noll decided to programme the computer to create art deliberately, drawing on his past training in cartoon and interests in abstract painting. He described the results in an internal published Technical Memorandum "Patterns by 7090" dated Baronial 28, 1962.[7]

Noll'due south early pieces combined mathematical equations with pseudo randomness. Today his work would exist called programmed computer art or algorithmic fine art. Much art is produced today by drawing and painting directly on the screen of the estimator using programs designed expressly for such purposes.

Ii early works by Noll were "Gaussian-Quadratic" and "Vertical Horizontal Number Iii." Stimulated past "op fine art," he created "Ninety Parallel Sinusoids" as a reckoner version of Bridget Riley's "Currents." Noll believed that in the figurer, the creative person had a new artistic partner.[viii] Noll used FORTRAN and subroutine packages he wrote using FORTRAN for all his art and animation.

Leon Harmon and Kenneth C. Knowlton – both researchers at Bell Labs -- perfected a computer technique in the mid 1960s in which a picture would be digitized, converted into a finite series of gray-calibration values, and so a small pixilated image assigned to each grey scale value. Harmon suggested the technique and Knowlton programmed and perfected information technology.[9] The final mosaic was fatigued on the microfilm plotter. Usually small images (in an 11x11 or a 15x15 matrix) of transistors and other electronic circuit elements, or some other richer variety of small images, were used to create the gray scale. Since the graphic output from the SC-4020 was non that large, a number of frames would be pasted together to create a bigger picture on a large panel.

The technique was used to digitize and pixilate (using an 11x11 matrix of pocket-size images, more often than not electric and electronic circuit elements) a pic of a reclining nude in 1966. Harmon took the photo and collaborated with Knowlton in creating "The Nude" – blown upward to a 5-foot by 12-human foot enlargement from the computer-generated microfilm – and which received publicity in The New York Times. (Oct eleven, 1967)[10] [11] "The Nude" was shown in the Museum of Modernistic Art's The Machine equally Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age in 1968.[12] Knowlton relates how they tossed a coin to determine who would be listed in the museum catalogue every bit the "artist" (Harmon) and as the "engineer" (Knowlton). Another of the many reckoner-generated images thus created was called "Gargoyle."

Knowlton recalls that the Public Relations department initially advised that "The Nude" could be circulated, but must not exist associated with Bell Labs. But once it appeared in The New York Times, the PR folks manifestly decided that it was not pornography, only "Art," and advised Harmon and Knowlton that wherever it appears, be sure to let people know it was done at Bell Telephone Laboratories, Incorporated.

Expanding upon his childhood interest in 3D stereo viewers, Noll programmed the computer at Bell Labs to calculate and and so depict on the microfilm plotter 35-mm images for the left and right centre of diverse "sculptures" combining elements of mathematical social club with computed randomness.[13] [xiv] He also used the 3D programs to plot scientific information.[xv] Noll suggested that this 3D stereoscopic computer technique could exist used by sculptors to visualize a work before rendering it to stone or metal, or by architects in designing and visualizing structures.

Early Computer Animation [edit | edit source]

A 35-mm camera captured the images drawn on the faceplate of the cathode ray tube in the Stromberg Carlson microfilm plotter. Thus a serial of images could exist programmed and drawn on the plotter to create a movie, thereby creating early on computer animation. Like blitheness was besides done using a Stromberg Carlson plotter at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory in California – although this was not known at the time the work was done at Bell Labs. The earliest work done at Bong Labs was to display scientific data – however, artistic animation came soon later.

Edward E. Zajac – a researcher at Bong Labs – programmed the IBM computer to create a movie showing a communication satellite orbiting nearly the Globe as its gyros stabilized its move.[16] This very early estimator-blithe motion-picture show was made in 1963 and was titled "Simulation of a Two-Gyro Gravity-Gradient Attitude Control System."[17] It stimulated work by many others at Bell Labs in creating computer-animated movies for scientific purposes. His movie was an creative demonstration to the public of what he had learned from his mathematical simulation of the gyros in stabilizing a satellite.

Frank W. Sinden – a mathematics researcher at Bong Labs – programmed the IBM computer in 1965 to create a movie showing how force and mass interacted to create movement.[18] The moving-picture show "Force, Mass and Motion"[19] was a sit-in to the public of physics and an early example of the educational possibilities of figurer blitheness.

In 1962, programmer Robert J. Tatem (working at the Whippany, NJ military R&D facility of Bell Labs) recalls that used the SC-4020 to create a 5-minute computer-animated film showing the "effects of a nuclear explosion on soil at footing null."[20] Three filmstrips were created, 1 for each main color, and they were then combined optically to create a final color movie – the first color computer-animated pic to be made at Bell Labs.

Others using computer animation for scientific and public educational purposes at Bell Labs included Joseph B. Kruskal, Jr., who made a movie to evidence the results as his multidimensional scaling algorithms converged on a solution. Robert G. McClure made a security-classified movie to show the results of simulations of a cloud of enemy ballistic missiles and decoys.

Kenneth C. Knowlton constructed a new programming linguistic communication called BEFLIX (a takeoff on "Bell Flicks") in 1963.[21] [22] The BEFLIX linguistic communication manipulated bitmaps of imagery, moving blocks of pixels efficiently and effectively. Knowlton used BEFLIX to create a computer-blithe movie in 1964 about how to make a computer-animated movie. [23]

Animator Stan VanDerBeek came to Bell Labs around 1965 equally a company to work with Knowlton using BEFLIX to create artistic movies, such as "PoemField #two."[24] Knowlton and VanDerBeek created a series of "PoemField" animated movies from around 1965 to the cease of 1969 (numbered 1 through 10). These ten films were fabricated with Knowlton's "TARPS" language (Two-D Alphanumeric Raster Picture System, a set of macros based on BEFLIX). Knowlton made TARPS specifically for VanDerBeek to employ for the "PoemField" films. [25]

In 1967, VanDerBeek and Knowlton created a computer-animated movie "Human being and His Globe" for the Globe's Off-white in Montreal. For all these collaborative movies (co-credited to VanDerBeek and Knowlton), Knowlton did nearly of the programming, and VanDerBeek added color, music, and editing to create the final pic, but co-ordinate to Knowlton, "After a few months, VanDerBeek became quite proficient with TARPS; in due time he was programming almost completely on his own, while I served essentially as a debugging consultant".[26] [27]

The movies made by Knowlton and VanDerBeek all take a somewhat similar way from the utilise of BEFLIX to motion blocks of pixels. BEFLIX'south gray-scale and expanse-filling pixels were further augmented by common geometric commands (such equally lines, arcs, circles) and the system fabricated more portable by programming it in FORTRAN.[28]

After L6 and TARPS, Knowlton went on to develop the EXPLOR (pictures based on Explicit Patterns, Local Operations and Randomness) linguistic communication.[29] After working with VanDerBeek, Knowlton collaborated with other artists, and his reckoner animation fashion connected to develop and became more sophisticated, and then besides did his software, culminating with MINI-EXPLOR, entirely written in FORTRAN for mini and larger computers.[thirty] A Knowlton four-color prototype, fabricated with EXPLOR, was one of the half-dozen calculator-generated serigraphs of a limited-edition portfolio "Art Ex Machina"" prepared and sold by creative person Gilles Gheerbrant of Montreal.[31]

A. Michael Noll programmed 3D stereoscopic computer animation in 1965.[32] Some of the films he created included a pseudo random object that inverse its shape, a computer-generated ballet of stick figures,[33] and the 3D projection of a rotating four-dimensional hypercube.[34] He later extended this 4-dimensional technique to words placed in a four-dimensional space that were then rotated and projected prospectively to a ii dimensional movie. This technique was used to create the animated title sequence for the 1968 film "Incredible Machine."[35] Virtually a year later, Noll used the technique to create the animated championship sequence for the NBC color special "The Unexplained," written past Arthur. C. Clarke.

The stereoscopic reckoner-animation was used to testify in 3D the simulated move of the basilar membrane in the human being ear.[36] Robert C. Lummis, Noll, and Human Mohan Sondhi fabricated this 1966 movie, which was a scientific application of the technique devised to create 3D computer art. The 3D software was also used to generate the perspective images required to make a calculator-generated hologram, using 1 of Noll's 3D random art as the subject.[37]

The optical attachment that facilitated stereoscopic viewing of the computer-animated stereo movies was the Prism-Stereo device, manufactured past Tri-Delta Applied science of Off-white Lawn, NJ. The left and correct binocular images were plotted head-to-head on each frame by the estimator and SC-4020, and then separately projected by a prism through polarized filters in the Prism-Stereo adapter, which was attached to the lens of the movie projector, for viewing with polarized spectacles.

Knowlton developed a programming language for linked lists, called L6 (Laboratories Low-Level Linked List Language).[38] In 1966, he used his BEFLIX linguistic communication to make a computer-animated movie showing the bones principles of L6 and how to use it.[39] The itch protrude is a an artistic touch in this early computer-made educational motion picture – an early demonstration of six-legged articulated animation (Fig. 9).

In 1966, a symposium entitled "The Human Use of Calculating Machines" was held at Bell Labs in Murray Hill, by invitation only to academics. The computer animated films past Zajac, Sinden, Knowlton, and Noll were shown. The graphic logo for the briefing was a computer-generated work by Noll.

Experimental Aesthetics [edit | edit source]

In 1965, Noll programmed the computer to create an image consisting of horizontal and vertical parallel black bars within a circle. The bars were placed at random, with a density called to mimic a painting by the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian.[40] In what became a classic experiment, Noll showed reproductions of both the computer image and the painting to people at Bell Labs. The majority preferred the reckoner image and believed it to be created by Mondrian.[41] The work "Computer Composition with Lines" was awarded outset prize in the annual computer art competition conducted past Edmund C. Berkeley's magazine Computers and Automation.[42]

Noll later on created a series of variations with varying amounts of pseudo randomness to use as stimuli in an experiment to determine whether people had a preferred selection. [43] The artistic preparation of the subjects had no effect on their artistic preferences, and each subject had a unique preference scale.

In nevertheless some other experiment performed around 1965-66, Noll showed 2nd and 3D images that combined gild with randomness to determine aesthetic preferences.[44] The 3D stereoscopic version was preferred over the apartment 2D version, and the more ordered images were the least preferred.

The Howard Wise Show [edit | edit source]

Bela Julesz was a enquiry scientist working at Bell Labs in the expanse of visual perception. He used the microfilm plotter to create stereograms in which each separate image for each eye was totally random, yet an image of an object would appear when viewed stereographically.[45] Julesz called these patterns random-dot stereograms. His research received much publicity and came to the attention of Howard Wise, who operated a renowned art gallery on West 57th Street in New York City. Wise liked to showcase what he considered new directions in art, such as Gerald Oster'due south op-fine art. Wise had seen Julesz's random-dot patterns on the cover of Scientific American mag.[46]

Wise contacted Julesz and asked to showcase the random-dot stereograms. Julesz then added Noll'southward estimator art to the show "Computer Generated Pictures." The works past Julesz and Noll were shown from April eight-24, 1965, and included not merely 2D works but also 3D works past both Julesz and Noll, which were viewed stereoscopically using polarized glasses. Julesz'due south works were the random-dot images he used for his research into human vision; Noll'south works were the images he made solely for artistic purposes. The New York Times review of the show stated, "The wave of the future crashes significantly at the Howard Wise Gallery … Freed from the tedium of technique and the mechanics of picture making, the creative person will just 'create.'" [47] The agreement was that any profits from the sale of the works would exist split betwixt the Wise Gallery and either Julesz or Noll. In the cease, not a single work was sold.

The random-dot images created by Julesz were solely for scientific purposes as stimuli for his investigations of binocular vision. However the images themselves had artistic value, which was recognized by Howard Wise. Julesz did not create the images as fine art – but since the images were shown every bit art, did that make Julesz an artist? Noll'due south works were created equally art – not for scientific purposes. Did that make Noll any more of an artist than Julesz? Jokingly, Julesz and Noll used to greet each other every bit a "fellow artiste."

Since AT&T did not want publicity that scientists at Bell Labs were creating art, Julesz and Noll were told to copyright all the works in their names. This was done to avert mention of Bell Labs and also to restrict the media from copying the works and publicizing them.

Knowlton recalls that the Public Relations department initially advised that "The Nude" could be circulated, but must non be associated with Bong Labs. Just once information technology appeared in The New York Times, the PR folks patently decided that it was not pornography, just "Art," and advised Harmon and Knowlton that wherever it appears, be sure to let people know information technology was washed at Bong Telephone Laboratories, Incorporated.

Later in 1965, many of Noll's works from the Wise show were exhibited at the Autumn Joint Computer Conference (FJCC) of the American Federation of Information Processing Societies (AFIPS) in Las Vegas from Nov 30 to December 1, 1965. Analog computer art by Maughan Mason was exhibited forth with Noll's digital computer art.

Very early estimator art used analog computers that were configured using cables and settings on knobs. Computer art created with digital computers came later in the early on 1960s. For this reason, dorsum then the prefix "digital" was oftentimes placed in front of "figurer art." Both analog and digital computer art were exhibited together at the 1965 Las Vegas conference.

Other Visitors and Employees [edit | edit source]

Although he himself did not produce any computer art or animation, Bell Labs engineer Billy Klüver collaborated with creative person Jean Tinguely in producing a one-time exhibit of a self-destructing machine at the Museum of Modern Art. Subsequently, Klüver and Robert Rauschenberg organized Experiments in Art and Technology (Swallow) in 1966 to put artists in contact with engineers and scientists at Bell Labs and other institutions for collaborative creative ventures.

Bong Labs scientist Jerry Spivack created an interactive art piece titled "Estimator Descending a Staircase." which was selected by Swallow for exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum toward the end of 1968. The interactive slice was comprised of three slides created past the SC-4020 plotter with each slide consisting of squares with random gray scales. Each square was filtered into RGB colors with the intensity of each colour controlled with knobs by the person viewing the overlapping three slides, resulting in the observer becoming transformed into the artist.

Bell Labs physicist Manfred R. Schroeder, working with programmer Sue Hanauer, programmed the SC-4020 plotter to draw images based on number theory. The complex images showed the patterns created by the equations and were exhibited at the Brooklyn "Some New Ancestry" show in 1968.[48]

Researcher Carol Bosche worked with Bela Julesz on experiments in stereopsis. She modified Knowlton's BEFLIX language to generate "patterns, using randomness in conjunction with symmetries and periodicities."[49]

Schroeder headed the inquiry area in which Noll worked and in which the interactive DDP-224 computer was installed and managed past Peter B. Denes (assisted by Ozzie Jensen and Barbara Caspers), primarily for speech communication research.

A raster browse display using a television monitor was invented and designed in 1969 by Noll (assisted past engineer D. Jack Maclean) for the DDP-224 (Calculator Command Visitor and after Honeywell) dedicated laboratory computer installation.[fifty] Initially monochrome, a color monitor was afterward added, allowing straight color graphics from the computer.

Aaron Marcus, then a graduate graphic design pupil in the Graphic Blueprint Department at Yale University's School of Art and Compages, who had studied FORTRAN programming at that place, initially worked as a summer enquiry intern at Bell Labs during the summertime of 1967. He was a graphic designer whose research projection at the Labs involved how to perform overall page layout and design using an interactive DDP-224 computer system. This project connected for a few years after Marcus took a position at Princeton University. Beginning in 1967, Marcus programmed the mainframe GE and IBM computers and microfilm plotter to create creative images with geometric patterns based on mathematical algorithms.[51] [52]

The video creative person Nam June Paik initially visited Bell Labs in late 1966 to larn virtually computer fine art and blitheness from Noll. Max V. Mathews and Noll visited Paik's studio on Canal Street in New York City. Paik learned FORTRAN programming from James Tenney and Noll, and Paik then programmed works, including computer animations, in 1967 and 1968.[53] All the same, the algorithmic aspects of programming were far from the analog easily-on approach to his video fine art. Charlotte Moorman, who directed the yearly summer Avant Garde Festival in New York Urban center, also visited Bell Labs to learn about the figurer art and blitheness research.

Expanding upon the educational application of computer animation initiated by Zajac and Sinden, Professors William H. Huggins of Johns Hopkins University and Don Weiner of Syracuse University visited Bell Labs for a few months effectually 1967 to make an educational film. Their picture, using the SC-4020, illustrated harmonic phasors and waveforms for electrical-technology educational activity.

Figurer Music [edit | edit source]

The history of computer music at Bell Labs has been well documented and is not the purpose of this history of calculator art at Bell Labs. Just a brusque mention of it seems warranted. Digital figurer music was pioneered and championed at Bell Labs by researchers Max V. Mathews and John R. Pierce.[54] A number of visiting composers were allowed to apply the computer facilities at Murray Hill during the hours when the computers were non beingness used for enquiry and other official work. Some of these visiting composers were James Tenney, Jean Claude Risset, Emmanuel Ghent, and Laurie Spiegel. Other researchers at Bell Labs who used the computers there to compose music were Joseph P. Olive, F. Richard Moore, and Joan Due east. Miller.

During the mid 1960s, musicians such a Leopold Stokowski and the conductor Hermann Scherchen visited Bell Labs regarding the computer music inquiry that was beingness done at that place. Scherchen observed that he could create music just as well using audio oscillators at his electronic music studio in Switzerland. But he was impressed by the computer blitheness, which he believed could be washed in no other manner. Interestingly, Roy Disney visited Bell Labs and was shown the computer animations but saw no application of the technology to the Disney studio.

Discussion & Conclusion: Artist-Technician [edit | edit source]

The distinction between fine art and technology was quite blurred during these early years of computer fine art and blitheness. The artistic application was sometimes used to motivate the development and awarding of the software and technology.

The artistic works of Noll and Marcus were done individually. Noll believed that the creative person should acquire the computer technology and how to program and utilise it – he was not a fan of collaboration, such as promoted by Klüver'south Swallow.[55] Noll and Marcus knew how to program and fabricated all artistic judgments themselves.

Virtually of the artistic films created by Knowlton were done collaboratively with diverse artists. Nevertheless, Knowlton created his earliest computer animations alone, and a clear style emerges that permeates about of the latter works that were done collaboratively. Knowlton was an agile artistic partner in these collaborations rather than just a programmer technician. Even so, Knowlton felt that "On calculator art I've usually lacked the courage to work entirely solitary…and trusted [the artists'] judgment for the final form of the films."[56] But without Knowlton, i may doubt whether whatsoever of these artistic computer-animated films would have been created; his calculator languages, and his programming in them, were crucial. Despite his early modesty in questioning whether he was an artist, Knowlton would afterwards acknowledge that he was becoming an artist, as demonstrated by his mosaics. [57]

Both Knowlton and Noll went on to invent and develop novel computer hardware and software for the interactive DDP-224 reckoner facility at Bell Labs: Knowlton - a virtual keyboard;[58] and Noll - a tactile, haptic "virtual reality" arrangement.[59] Knowlton conceived a musical "trounce that seemed to endlessly speed up (or deadening down)," which was implemented by Laurie Spiegel.[sixty] [61]

Acknowledgements [edit | edit source]

This history was written, edited, and researched by A. Michael Noll. Jerry Spivack, Kenneth C. Knowlton, Laurie Spiegel, Aaron Marcus, and others who contributed information and documentation. The AT&T Athenaeum and AT&T Tech Channel were boosted sources of documentation. Searches of the Net supplied farther supporting information and details, every bit needed and for checking sources.

References [edit | edit source]

- ↑ Rockman, Arnold and Leslie Mezei, "The Electronic Reckoner equally an Artist," Canadian Art, Vol. XXI, No. half dozen (Nov/Dec 1964), pp. 365-367.M

- ↑ Krampen, Martin and Peter Seitz (Eds.), Design and Planning two: Computers in Design and Communication - 1966 International Conference on Design and Planning at the University of Waterloo.

- ↑ Reichardt, Jasia (ed), Cybernetic Serendipity, the estimator and the arts, Studio International Special Result, No. 905, November 1968, London England and exhibition "Cybernetic Serendipity" held in 1968 in London at the Institute for Contemporary Arts. http://computer-arts-society.com/history

- ↑ http://computer-arts-guild.com/history

- ↑ Bell Labs Memoirs: Voices of Innovation, co-edited by A. Michael Noll and Michael Geselowitz, IEEE History Centre (New Brunswick, NJ), printing by Amazon, 2011.

- ↑ Gertner, Jon, The Idea Mill: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation, Penguin Press, 2012.

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, BTL Technical Memorandum MM-62-1234-14, "Patterns past 7090," Baronial 28, 1962.

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, "The Digital Estimator as a Creative Medium," IEEE Spectrum, Vol. 4, No. x, (October 1967), pp. 89-95.

- ↑ Harmon, Leon, "The Recognition of Faces," Scientific American, Vol. 229, No.5 (November 1973), pp. 71-82.

- ↑ Knowlton, Kenneth C., "Portrait of the Artist as a Immature Scientist," YLEM Periodical, Vol. 25, No. 2 (2005) [i].

- ↑ Lieberman, Henry R., "Art and Science Proclaim Alliance in Avant-Garde Loft," The New York Times, Oct eleven, 1967, p. 49.

- ↑ Hultén, K. Yard. Pontus, The Motorcar every bit Seen at the Stop of the Auto Age, The Museum of Mod Art (New York), 1968, p. 207.

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, BTL Technical Memorandum MM-64-1234-2, "Stereographic Projections by Digital Calculator," March 27, 1964.

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, "Stereographic Projections by Digital Calculator," Computers and Automation, Vol. xiv, No.5, (May 1965), pp. 32-34.

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, "Computer Graphics in Acoustics Research," IEEE Transactions on Audio and Electroacoustics, Vol. AU-xvi, No. 2, (June 1968), pp. 213-220).

- ↑ Zajac, Edward East., "Computer-fabricated perspective movies as a scientific and communication tool," Communications of the ACM, Vol. 7, Issue three (March 1964), pp. 169-170 & "Calculator animation: A new scientific and educational tool," Journal of the Society of Motility Picture Television receiver Engineers, Vol. 74, pp. 1008-1008 (Nov 1965).

- ↑ http://techchannel.att.com/play-video.cfm/2012/7/xviii/AT&T-Archives-Outset-Reckoner-Generated-Graphics-Flick

- ↑ Sinden, Frank W., "Constructed Cinematography," Perspective Vol. 7, pp. 279-289 (1965).

- ↑ http://techchannel.att.com/play-video.cfm/2012/8/20/AT&T-Athenaeum-Strength-Mass-Movement

- ↑ Unpublished Tatem autobiography and telephone interview on January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Knowlton, Kenneth C., "A figurer technique for producing blithe movies," Proceedings of the AFIPS Spring Joint Computer Conference, April 21-23, 1964, pp. 67-87. "BEFLIX, A Programming Language for Producing Animated Diagram Movies," TM63-1271-6 (1963), Bell Telephone Laboratories; and "BEFLIX-2, An Improved Programming Language for the Production of Animated Movies," TM63-1271-9 (1963), Bell Telephone Laboratories.

- ↑ Knowlton, Kenneth C., "Calculator-Animated movies," in Emerging Concepts in Figurer Graphics, E. Secrest and J. Nievergelt, eds., W. A. Benjamin, New York, 1968, pp. 343-370.

- ↑ "A Computer Technique for the Production of Blithe Movies" http://techchannel.att.com/play-video.cfm/2012/9/ten/AT&T-Athenaeum-Computer-Technique-Production-Animated-Movies

- ↑ http://techchannel.att.com/play-video.cfm/2012/8/13/AT&T-Archives-Poem-Field-two

- ↑ E-mail dated June 23, 2013 from Kenneth C. Knowlton to Noll.

- ↑ Knowlton, Kenneth C., "Collaborations with Artists – A Programmer's Reflections," in Graphic Languages, F. Nake and A. Rosenfeld, eds., N-Holl Pub, London, 1972.

- ↑ Knowlton, Kenneth C., "On the Frustrations of Collaborating with Artists," SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics, Vol. 35, No. three (August 2001), pp. 20-22.

- ↑ Knowlton, Kenneth C. and Lorinda L. Ruby, "FORTRAN Iv BEFLIX", Proceedings of the 8th Annual Meeting of the Users of Automatic Data Display Equipment (UAIDE), November 1969, pp. 411-431.

- ↑ Knowlton, Kenneth C., "EXPLOR — A Generator of Images from EXplicit Patterns, Local Operations & Randomness," Proc. 9th Annual UAIDE Mtg., pp. 544-583 (1970).

- ↑ Knowlton, Kenneth C., "MINI-EXPLOR: a FORTRAN-coded version of the EXPLOR language for mini (and larger) computers," ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics, Vol. nine, No. 3 (Fall 1975), pp. 31-42.

- ↑ Run into: http://dada.compart-bremen.de/item/agent/60

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, "Reckoner-Generated Iii-Dimensional Movies," Computers and Automation, Vol. 14, No. 11, (November 1965), pp. 20-23.

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, "Choreography and Computers," Dance Magazine, Vol. XXXXI, No. 1, (January 1967), pp. 43-45. The estimator-generated ballet was featured in an episode of the BBC "Tomorrow's World" past Derek Cooper, which aired in England on December half-dozen, 1968, and included early reckoner animations by a number of others.

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, "Computer Blitheness and the Fourth Dimension," AFIPS Briefing Proceedings, Vol. 33, 1968 Fall Joint Computer Briefing, Thompson Book Company: Washington, D.C. (1968), pp. 1279-1283.

- ↑ http://techchannel.att.com/play-video.cfm/2011/4/22/AT&T-Athenaeum-Incredible-Machine

- ↑ This 3D movie was the topic of a Bell Telephone Laboratories Report advertisement "A iii-D Glimpse of the Hearing Procedure" and can be seen on YouTube at: http://www.youtube.com/spotter?5=yADT4gvzwE4

- ↑ King, 1000. C., A. Michael Noll, and D. H. Berry, "A New Approach to Computer-Generated Holography," Applied Eyes, Vol. 9, No. 2, (February 1970), pp. 471-475.

- ↑ Knowlton, Kenneth C., "A Programmer's Description of Lhalf-dozen " Comm. ACM, Vol. 9, No. 8 (Baronial 1966), pp. 616-625.

- ↑ http://techchannel.att.com/play-video.cfm/2012/viii/6/AT&T-Athenaeum-L6-part-I-Bell-Laboratories-Low-Level-Linked-Listing-Linguistic communication

- ↑ Taylor, Grant, "Routing Mondrian: The A. Michael Noll Experiment," Media-N (The Periodical of the New Media Caucus), Vol. 08, No. 02 (Fall 2012), http://median.s151960.gridserver.com/?page_id=689

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, "Homo or Automobile: A Subjective Comparing of Piet Mondrian's 'Composition with Lines' and a Computer–Generated Moving-picture show," The Psychological Record, Vol. xvi. No. i, (Jan 1966), pp. 1-10.

- ↑ Computers and Automation, Vol. 14, No. 8 (Baronial 1965), front end cover & pages 3 & iv.

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, "The Effects of Artistic Training on Aesthetic Preferences for Pseudo-Random Computer-Generated Patterns," The Psychological Tape, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Fall 1972), pp. 449-462.

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, "Computers and the Visual Arts," Design and Planning two: Computers in Design and Communication (Edited by Martin Krampen and Peter Seitz), Hastings House, Publishers, Inc.: New York (1967), pp. 65-79.

- ↑ Julesz, Bela, "Visual Design Discrimination," IRE Transactions on Information Theory, Vol. 8, No. 2 (1962), pp. 84-92.

- ↑ Julesz, Bela, "Texture and Visual Perception," Scientific American, Vol. 212, No. 2 (Feb 1965), pp. 38-48.

- ↑ Preston, Stuart, "Art ex Machina," The New York Times, Sun, Apr 18, 1965, p. X23.

- ↑ Schroeder, Manfred R., autobiography in Bong Labs Memoirs: Voices of Innovation, (Edited past A. Michael Noll & Michael Geselowitz), IEEE History Heart (2011), pp. 88-89; and "Lasers, Computers Star in Mod Art Shows," Bell Labs News, Vol. VIII, No. 21 (November xv, 1968).

- ↑ Bosche, Carol, "Figurer Generated Random Dot Images," in Krampen, Martin and Peter Seitz (Eds.), Design and Planning ii: Computers in Pattern and Communication - 1966 International Conference on Design and Planning at the University of Waterloo, pp. 86-91

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, "Scanned-Display Computer Graphics," Communications of the ACM, Vol. xiv, No. 3, (March 1971), pp. 145-150.

- ↑ Marcus, Aaron, "The Computer and the Creative person," Eye, Vol. two, pp. 36-39 (Spring 1968).

- ↑ Marcus, Aaron, "The Designer, the Computer, and 2-Mode Communication Organization," Impress, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 34-39 (1971).

- ↑ Moonan, Wendy, "Back to the Futurity," Smithsonian Magazine, Vol. xl, No. one (Apr 2015), p. 14. Gregory Zinman has discovered many reckoner programs and letters from the 1966-68 menstruation by Nam June Paik in the holdings of the Paik Archive at the Smithsonian American Art Museum every bit well equally those at the Nam June Paik Estate.

- ↑ Mathews, Max Five., Joan E. Miller, F. R. Moore, J. R. Pierce, J. C. Risset, The Technology of Computer Music, The MIT Printing, 1969.

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, "Art Ex Machina," IEEE Student Journal, Vol. 8, No. four, (September 1970), pp. ten-14.

- ↑ McCauley, Carole Spearin, "It'south an Hazard Really!" in Computers and Creativity, Praeger Publishers, New York, 1974, pp. 92.

- ↑ See: www.knowltonmosaics.com.

- ↑ Knowlton, K. C., "Computer Displays Optically Superimposed on Input Devices," Bell System Technical Journal, March 1977, pp. 367-383 and U. Southward. Patent 3,879,722 "Interactive Input-Output Estimator Concluding with Automatic Relabeling of Keyboard."

- ↑ Noll, A. Michael, "Homo-Machine Tactile Communication System," SID Journal, (The Official Journal of the Social club for Information Display), Vol. one, No. 2 (July/August 1972), pp. five-xi; and U. Due south. Patent 3,919,691 "Tactile Human-Machine Communications Organisation."

- ↑ Risset, Jean-Claude, "Rhythmic Paradoxes and Illusions: a Musical Illustration," International Computer Music Conference Proceedings (ICMC 1997), pp. vii-10.

- ↑ Knowlton, Kenneth C., "A Cyclic Rhythm Perceived as 'Always-Accelerating,'" Bell Telephone Laboratories, internal memorandum, March 4, 1976.

Source: https://ethw.org/First-Hand:Early_Digital_Art_At_Bell_Telephone_Laboratories,_Inc

0 Response to "Computers and Automation Vol 18 No 9 August 1969 Computer Art"

Post a Comment